Saint Peter’s Tomb: Is Peter Really Buried in the Vatican?

Written by Marko Marina, Ph.D.

Author | Historian

Author | Historian | BE Contributor

Verified! See our guidelines

Verified! See our editorial guidelines

Date written: November 13th, 2025

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily match my own. - Dr. Bart D. Ehrman

I remember visiting beautiful Rome for the first time years ago. On the bus heading toward the Vatican, a number of people were visibly thrilled, whispering to one another that they were about to visit the place of Saint Peter’s tomb.

The thought of standing near the resting place of one of Jesus’ closest disciples (the one whom, according to the tradition of the Catholic Church, had been chosen to lead the community of believers after Jesus’ death) filled them with awe.

Sitting there as the bus rolled toward the “eternal city,” I must admit that I shared their excitement. After all, it’s not every day that one has the chance to enter St. Peter’s Basilica and stand so close to what countless generations have believed to be the burial place of the Apostle Peter.

Yet years later, as I delved deeper into the study of early Christianity, I discovered that the question of whether Peter truly ended his life in Rome, and whether his remains really rest beneath the Vatican, is far more complex than most visitors realize.

The story behind St. Peter’s tomb is one that intertwines faith, tradition, legend, and archaeology. It’s a fascinating blend of historical evidence and devotional tradition that continues to inspire both scholars and pilgrims alike.

In this article, I’d like to explore that story. We’ll begin by revisiting what we can actually know about Peter himself, the Galilean fisherman turned apostle whose life and character we glimpse through the pages of the New Testament.

Then we’ll turn to the traditions surrounding his death and martyrdom, tracing how those stories emerged and evolved. Finally, we’ll descend, figuratively speaking, beneath the marble floors of St. Peter’s Basilica, to examine the centuries-old claim that the apostle’s bones lie there still.

But before we begin, make sure to check out Bart Ehrman’s captivating course “Paul and Jesus: The Great Divide.” In the eight amazing lectures, Dr. Ehrman provides a comparative analysis of two most important figures in the history of Christianity. If you think that Paul and Jesus would get along, this course is for you!

Apostle Peter in the New Testament: A Brief Look

Before we get into the issue of St. Peter's tomb, we have to take a look at his life. What can we know about him? To understand anything about the life and death of St. Peter, we have to take a hard look at the nature of the sources we have.

And, as you can imagine, they are far from what a historian would like to have. In his book Peter, Paul, and Mary Magdalene, Bart Ehrman explains:

(Affiliate Disclaimer: We may earn commissions on products you purchase through this page at no additional cost to you. Thank you for supporting our site!)

The narratives that we have—for example, the Gospels and Acts—probably do contain some historical recollections of things that actually happened in the life of Peter (and of Mary, and of Jesus, etc.). But they also contain historically inaccurate statements, many of which are made for the same reasons that the more accurate ones are made: not in order to provide us with history lessons about life in first-century Roman Palestine, but in order to advance important Christian points of view.

Working within that constraint and through a careful reconstruction of our sources, a somewhat coherent profile emerges.

Peter’s given name was Simon (Aramaic Shimʿon); “Peter” (Petros in Greek; Kephas/Cephas in Aramaic) functions as a nickname meaning “Rock.” He was a Galilean fisherman based in or around Capernaum, probably part of a small family enterprise with his brother Andrew.

The sources imply an ordinary social status (manual labor, modest means) and make it plausible that he was married (his mother-in-law is mentioned in the Gospel of Mark; Paul notes that Peter traveled with a wife in 1 Cor 9:5).

Given his milieu, he most likely spoke Aramaic and wasn’t formally schooled. Therefore, Acts’ description of Peter and John as “unlettered” fits what we, based on research done by scholars such as Catherine Hezser, know about literacy rates in rural Galilee.

Within the Gospel narratives, Peter stands out as both prominent and painfully human. He is consistently placed at the head of the Twelve and, more narrowly, within Jesus’ closest circle alongside James and John (e.g., Jairus’ daughter, the Transfiguration, Gethsemane).

He confesses Jesus as the Messiah yet almost in the same breath rebukes him for predicting suffering; he steps out in faith and then sinks; he vows loyalty and then denies knowing Jesus. Whether each scene preserves precise memory, the recurring pattern is striking and historically suggestive: Peter was the movement’s most visible insider, whose boldness could give way to fear under pressure

After Jesus’ death, the earliest Christian movement that coalesced in Jerusalem remembers Peter as a leading figure, one of the “pillars” alongside James (the Lord’s brother) and John.

In that aspect, Paul’s letters offer our earliest external window: they portray Peter primarily as a mission leader among Jews, in constructive (and sometimes tense) relationship with Paul’s gentile mission (Galatians 1-2).

The famous Antioch incident, where Paul says he opposed Peter “to his face,” is valuable precisely because it’s unflattering. To put it more bluntly, it suggests Peter could waver when communal and reputational pressures rose.

Moreover, the book of Acts then gives a theologically shaped portrait that magnifies his role in speeches and signs. As historians, we can use Acts, but only with caution! It’s not a neutral chronicle and often serves theological aims.

Finally, the familiar claim that Peter served as the “first bishop of Rome” reflects a later stage of ecclesiastical development rather than a title or office attested in our earliest sources. Peter almost certainly didn’t found the first community of Jesus’ followers in Rome.

Moreover, in the mid-1st century, the Christian movement there wasn’t organized under a single episcopal leader. As Peter Lampe has demonstrated in his landmark study From Paul to Valentinus: Christians at Rome in the First Two Centuries, the earliest Roman believers met in a number of small house congregations scattered across the city.

Most of these groups were loosely connected through shared belief in Jesus’ resurrection, mutual recognition, and (possibly) collective body of presbyters, but they lacked a centralized hierarchy or unified leadership structure (one bishop as the head of the entire city-community).

With this historically grounded sketch of Peter’s background and leadership in place, we can now turn to the next question: what, if anything, can be established about how and where he died? And how did those traditions eventually intersect with the centuries-long veneration of a specific burial site beneath St. Peter’s Basilica?

St. Peter’s Tomb: Traditions of Peter’s Death in Rome

Modern scholarship remains divided over what actually happened to Peter at the end of his life. On one side stands the hard minimalism of Michael Goulder, who, in his article “Did Peter Ever Go to Rome?” insists that the apostle never set foot in the “eternal city” and probably died in Jerusalem around 55 C.E.

According to this view, the complete silence of the New Testament about Peter’s death is decisive: if the author of Acts had known of such a dramatic event, he would have surely mentioned it.

On the opposite end lies the radical constructivism of Christian Grappe, who treats the stories about Peter’s fate not as historical memories but as fluid “images” that evolved to express different theological and ideological concerns of later communities.

As he writes in his study Images de Pierre aux deux premiers siècles (Images of Peter in the First Two Centuries):

“But the field of investigation that we wish to cover here—namely, the first two centuries of our era—will lead us to be concerned as much with the development of Peter as with his history. Instead of seeking to define the contours of a single face, to borrow one of the terms from our initial quotation, we shall endeavor to shed light on the evolution of the image—or rather the images—of the prince of the apostles, by tracing their trajectories over these two centuries. Within such an approach, there will be no need to assess primarily the reliability of this or that testimony concerning Peter, or its conformity with what may be glimpsed of the historical person. What will matter first is to treat each testimony as such, to take into account the image or images of the apostle that it presents, and to try to understand why, at a given moment and within a given milieu, one or more of these images were put forward. From this perspective, even a text that appears aberrant at first sight may prove to be of great value, for it reveals the particular interests of a group that did not hesitate to enlist Peter in order to legitimize its convictions, ideas, practices, or way of functioning. When compared with other documents, this will allow us to determine the issues with which the figure of the prince of the apostles was associated during the first two centuries.” (my translation)

In other words, for Grappe, the question of what actually happened is less important than how Peter’s memory was repeatedly reshaped to serve new purposes.

Between these poles of skeptical minimalism and literary symbolism stands a more moderate, historically engaged approach, the one represented by scholars such as Markus Bockmuehl.

He asserts that the earliest memories of Peter’s death, though refracted through faith and tradition, still deserve serious historical consideration. So, what do we know about Peter’s death in Rome?

The earliest surviving reference comes from the Roman letter, known as 1 Clement, written around 95 C.E. “Because of unjust jealousy,” the author says, “Peter bore up under hardships not just once or twice, but many times; and having thus borne his witness, he went to the place of glory that he deserved” (1 Clem 5:4).

While the statement is brief and lacking in detail, it presupposes that Peter’s martyrdom was common knowledge among its readers. The phrase “among us” that follows, referring to a “great multitude” who also suffered, most naturally evokes the Neronian persecution in Rome around 64 C.E.

Did You Know?

From Jerusalem to Rome: The Longest Stairway Move in History

If you ever visit Rome, you’ll probably be as surprised as I was when your tour guide starts talking about the Pilate Stairs. Wait…What? The stairs of Pontius Pilate? In Rome? As it turns out, according to tradition, the Scala Sancta (“Holy Stairs”) are the very steps Jesus supposedly climbed in Jerusalem during his trial before Pilate.

The story claims that they were transported to Rome by Saint Helena, Constantine’s mother, in the 4th century. It was one of several relics she is said to have brought back from the Holy Land.

Today, the Scala Sancta stands near the Lateran Palace, just across from the Basilica of St. John Lateran. Pilgrims ascend the twenty-eight marble steps on their knees, a devotional practice that has endured for centuries. The stairs are covered by protective wood panels, but small openings reveal the “original” stone, said to be stained by drops of Jesus’ blood.

Of course, no serious historian or archaeologist believes these are literally Pilate’s stairs. There is no evidence they ever came from Jerusalem, let alone from the praetorium where, according to the Gospels, Jesus was condemned. Still, the Scala Sancta remains one of Rome’s most evocative relic traditions. And I doubt that the thousands of pilgrims who have climbed those steps on their knees would feel any regret upon learning that the stairs aren’t authentic.

Later authors echo this same assumption: Ignatius of Antioch, writing early in the 2nd century, associates Peter and Paul with the church of Rome. Moreover, Dionysius of Corinth (c. 170 C.E.) explicitly names Rome as the site of both apostles’ deaths.

Finally, Tertullian takes their martyrdoms there as a settled fact. Even the apocryphal Acts of Peter, though legendary in its details, reflects a tradition already widespread, the one that proclaims that Peter was crucified in Rome.

Bockmuehl seeks to reassess this evidence by returning to what he calls the period of “living memory,” roughly the first two centuries after Peter’s death, when communities still retained personal and institutional recollections of the apostles.

Within that window, Bockmuehl observes, no ancient source locates Peter’s death anywhere other than Rome.

He argues that the testimony of 1 Clement, though restrained, fits precisely the kind of rhetorical reserve one would expect from a Roman Christian writing within living memory of Nero’s persecution.

The convergence of diverse witnesses (from East and West, from orthodox and heterodox circles) points to a shared and stable recollection rather than to a late Roman invention.

For Bockmuehl, the story’s durability across independent traditions and the absence of any rival claim elsewhere make it historically credible that Peter did, in fact, meet his death in Rome. Details such as the inverted crucifixion appear only in later 2nd-century texts like the Acts of Peter, but the core claim of a Roman martyrdom seems rooted in genuine early memory.

When viewed this way, the question of Peter’s death moves beyond simple faith or fiction. It illustrates how the earliest Christian communities preserved historical recollections through collective memory that, while never detached from theology, may still anchor us in real events.

Whether one approaches these traditions with full belief or cautious skepticism (I’m certainly leaning toward the latter option), the evidence suggests that Rome, more than any other city, became inseparable from Peter’s story in both history and devotion.

Having examined what we can reasonably know about Peter’s life and death, we can now turn to an even more tangible (and more contentious) question: what lies beneath the marble floors of St. Peter’s Basilica?

In other words, is Saint Peter’s tomb in the Vatican truly the final resting place of the apostle whose memory looms so large in Christian tradition?

Where Is Saint Peter’s Tomb: Assessing the Evidence

According to the church historian Eusebius, one of the earliest references to a specific site connected with Peter and Paul comes from the Roman presbyter Gaius, writing at the beginning of the 3rd century.

Addressing Proclus, the leader of the Cataphrygian sect, Gaius declared: “As for me, I can show you the trophies (τὰ τρόπαια) of the apostles. If you wish to go to the Vatican Hill or along the Ostian Way, you will find the trophies of those who founded this Church.”

This brief remark, offered almost in passing, provides the first historical witness to a physical location venerated as the resting place of the apostles Peter and Paul.

This casual comment probably represents the earliest mention of a specific location associated with St. Peter’s tomb. As Christian Grappe explains:

“The immediate context in which this notice appears… confirms that these are indeed the trophies of Peter and Paul. It also shows that the historian of Caesarea understood the term τρόπαιον in the sense of tomb, although it can equally designate a memorial intended to mark the place of an execution. In any case, we can infer from this testimony that in Rome, around the year 200, people did not content themselves merely with acknowledging that Peter and Paul had suffered martyrdom in the capital; they went so far as to point out specific sites that were regarded as the places of their execution or even, already, of their graves.” (my translation)

By the dawn of the 3rd century, then, the memory of Peter and Paul was already anchored to topographical points in the Roman landscape (the Vatican Hill for Peter, and the Ostian Way for Paul), suggesting that the cultic memory of both apostles had taken on a spatial and devotional form.

Roughly a century later, according to Christian tradition, the Roman emperor Constantine sought to honor the apostles by constructing magnificent basilicas over their supposed burial sites.

The story holds that, following his conversion and the Edict of Milan in 313 C.E., Constantine ordered the leveling of the Vatican slope, the construction of massive retaining walls, and the creation of a monumental platform over the existing necropolis.

The builders are said to have carefully preserved a small shrine or aedicula (believed to mark Peter’s grave) and to have positioned the basilica’s altar directly above it.

This is the traditional narrative, preserved in later sources such as the Liber Pontificalis, which portrays Constantine as the emperor who gave physical form to the apostolic memory of Rome.

Contemporary scholarship, however, has largely abandoned this view. As Timothy Barnes argues in Constantine: Dynasty, Religion and Power in the Later Roman Empire (2011), recent archaeological and textual analyses have shown that Constantine “did not found either Saint Peter’s on the Vatican or Saint Paul’s Outside the Walls either in 312 or later.”

While he indisputably constructed the Lateran Basilica and several other Roman churches, the evidence indicates that the great apostolic basilicas weren’t imperial projects initiated or completed under his reign.

Later generations, eager to associate these sacred sites with the first Christian emperor, likely retrojected his name onto building efforts that began or took shape after his death.

In any case, the archaeological rediscovery of this area came much later. In 1939, excavations beneath the present St. Peter’s Basilica were initiated following the accidental discovery of an underground void during the burial preparations for Pope Pius XI.

What archaeologists uncovered was a remarkably well-preserved Roman necropolis, with dozens of tombs dating to the first and second centuries. In its center stood a small, walled shrine known as the Trophy of Gaius, the very monument the 3rd-century presbyter had described.

The site also contained a complex of later Christian burials and graffiti walls inscribed with prayers and invocations, some referencing “Peter.” These finds confirmed that the veneration of Peter at this spot extended back to at least the second century, though they couldn’t, by themselves, prove the presence of Peter’s physical remains.

The question of the bones themselves proved more controversial. During the 1940s excavations, a box of human remains was discovered in a small niche near the aedicula.

Later, in the 1950s and 1960s, the Vatican archaeologist Margherita Guarducci argued that these bones (an assemblage of human fragments belonging to a single robust male of roughly the right age) had originally been kept in the shrine as the relics of St. Peter.

Her interpretation gained ecclesiastical support and, in 1968, Pope Paul VI announced the following:

“New and exceedingly careful investigations were subsequently carried out, and their results—confirmed, in our view, by the judgment of competent and prudent experts—lead us to a positive conclusion: the relics of Saint Peter have also been identified in a manner that we may consider convincing, and we express our praise to those who, with great attentiveness, learning, and long and arduous labor, have devoted themselves to this study” (translation courtesy of Petar Uškovic Croata)

Yet not all specialists agreed. Other archaeologists, such as Antonio Ferrua, one of the original excavation team, remained cautious, noting the complex stratigraphy, the uncertain provenance of the remains, and the lack of epigraphic proof.

In two separate essays published originally in La Civiltà Cattolica (17 March 1984; 3 March 1990) Ferrua was very critical, repeatedly stating that he “non aver potuto pubblicare” ("could not publish") all the information in his possession, which would have demolished the theory that Peter's bones were found under the Altar of the Confession.

Contemporary experts accept that early Christians revered this spot as Peter’s memorial but regard the identification of the bones as the apostle’s as possible, though far from demonstrable.

In other words, archaeology corroborates that Christian veneration centered on the Vatican Hill by the end of the 2nd century and that later believers were convinced they were honoring St. Peter’s tomb.

Still, absolute proof (whether through inscriptions or forensic data) remains elusive. What the evidence gives us is a chain of collective memory, rather than a verified historical and archaeological identity.

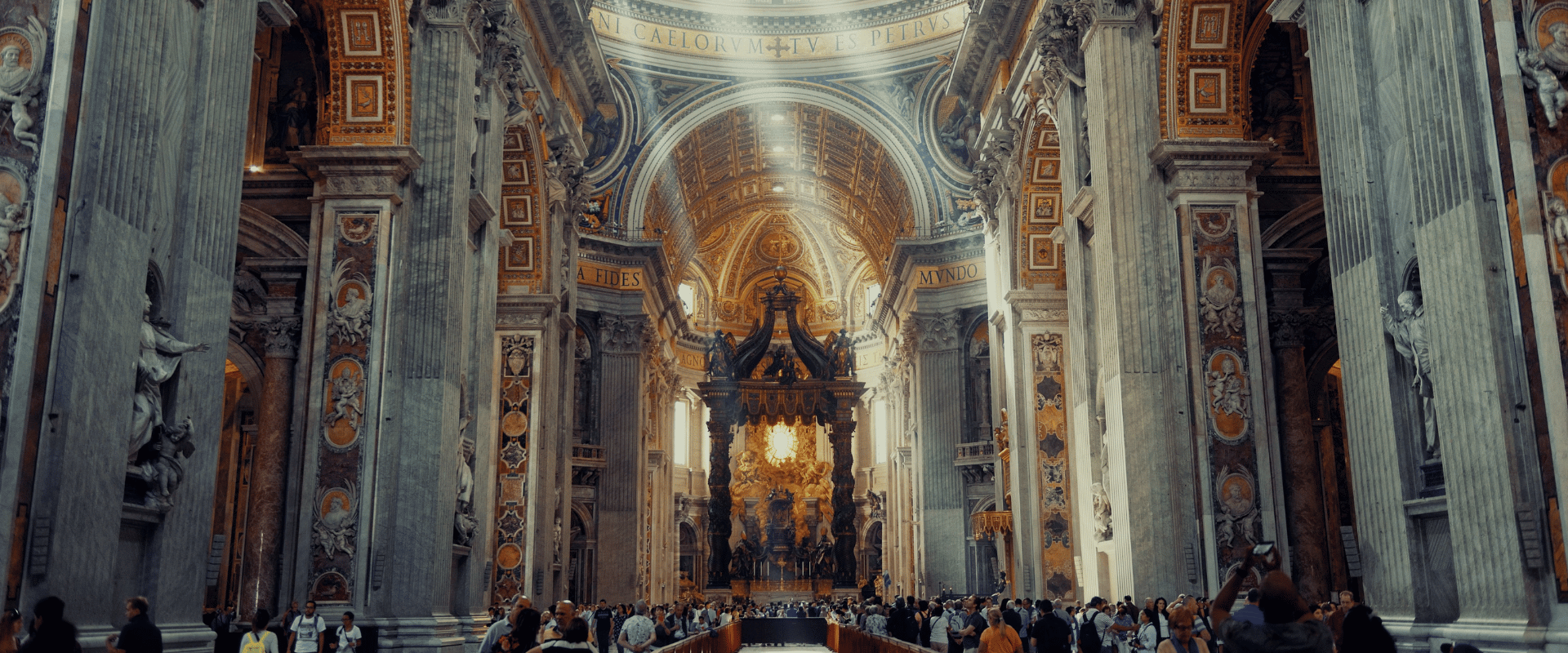

Can you visit St. Peter’s tomb? That’s a question still asked by many today. The answer is yes.

Deep beneath the basilica’s grand altar lies the Vatican Necropolis, a labyrinth of ancient mausoleums and narrow corridors.

Visits are strictly limited and must be arranged through the Vatican’s Ufficio Scavi, but standing before the modest red-plastered shrine that countless pilgrims have venerated for nearly two millennia offers a rare encounter between archaeology, memory, tradition, and faith.

Conclusion

Other trips I took to Rome didn’t include dozens of excited people waiting to see Saint Peter’s tomb, but the sense of beauty and historical depth that defines the city was still with us. Walking through its narrow streets, surrounded by ancient ruins and Renaissance domes, one can’t help but feel how profoundly history and memory coexist there.

Whether Peter himself was buried on the Vatican Hill or the site marks, instead, the memory of his veneration (I’m leaning toward the latter option!), the evidence (textual, archaeological, and traditional) reveals a remarkable continuity that influenced the subsequent history of the entire city!

From the late 1st century onward, Christians in Rome believed that the “prince of the apostles” (to borrow Grappe’s phrase) had died and been buried in their city. That belief shaped the city’s geography, inspired its earliest monuments, and eventually gave rise to the most famous church in the world.