Asherah in the Bible: Pole, Goddess, or Yahweh’s Wife?

Written by Marko Marina, Ph.D.

Author | Historian

Author | Historian | BE Contributor

Verified! See our guidelines

Verified! See our editorial guidelines

Date written: September 10th, 2025

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily match my own. - Dr. Bart D. Ehrman

Have you heard about Asherah? Most people would probably say no. Today, Judaism is typically grouped with Christianity and Islam as one of the world’s three great monotheistic religions. And rightly so! Modern Judaism is uncompromising in its insistence that there is only one God, the God of Israel.

But historians and anthropologists know that the story of ancient Israel’s religion is far more complicated. If we dig into the earliest layers of the Hebrew Bible, we find echoes of a time when the religious landscape wasn’t strictly monotheistic.

The Bible itself, surprisingly, bears traces of a past in which the boundaries between Yahweh, the God of Israel, and other divine beings weren’t yet sharply drawn.

This complexity is hardly unique to Israel. Ancient religions across the Near East evolved over centuries, often reshaping earlier traditions, incorporating foreign influences, and suppressing rival cults.

Egypt, Mesopotamia, Canaan had pantheons of gods and goddesses whose worship waxed and waned depending on politics, dynasties, and cultural shifts. We often forget that the Israelite religion didn’t emerge in a vacuum. It was part of this same world, deeply shaped by the broader polytheistic environment of the ancient Near East.

This is where the mystery of Asherah comes in. Was she merely a symbol, a sacred object, or an actual goddess once venerated alongside Yahweh? Did she play a role in Israel’s earliest religious traditions before being written out of the story? The evidence is tantalizing but fragmentary.

In this article, we’ll explore who or what Asherah was, examine the evidence that some ancient Israelites may have viewed her as Yahweh’s consort, and consider why her presence was eventually erased from the biblical tradition.

However, before we embark on the journey, it’s worth noting that biblical scholar Dan McClellan has produced a 100-minute lecture titled “The Lost Goddess of Israel: Rediscovering Asherah.”

In it, he examines the archaeological evidence, inscriptions, and biblical texts in detail, offering his own informed conclusions about Asherah’s identity and role in ancient Israelite religion. If you’d like to go deeper than we can here, his course is an excellent resource.

Asherah in the Bible: Who or What is an Asherah?

In her book The Cult of Asherah in Ancient Israel and Judah, Judith M. Hadley notes:

(Affiliate Disclaimer: We may earn commissions on products you purchase through this page at no additional cost to you. Thank you for supporting our site!)

Scholarly opinion differs widely concerning the identification of asherah, but can be broken down into two general categories: first, that the term “asherah” in the Hebrew Bible did not refer to a goddess at all, but described solely an object (either some type of wooden image, a sanctuary, a grove or a living tree); and secondly, that asherah could indicate both a wooden image and the name of a specific goddess.

This tension (between Asherah as a cult object and Asherah as a goddess) has been at the center of modern debates about Israelite religion. The difficulty is compounded by the fact that the biblical texts themselves often use the term without clarification, leaving interpreters to determine whether “asherah” denotes a physical symbol, a sacred place, or a divine figure.

Etymologically, the name “Asherah” likely derives from the root ʾšr, associated with uprightness or happiness, though the exact nuance remains debated. In the broader ancient Near Eastern world, Asherah is well-attested as a mother goddess and consort of the high god El in Ugaritic texts from Ras Shamra (ancient Ugarit).

Within the Hebrew Bible, however, the term occurs about 40 times, usually in contexts of condemnation.

Translators have rendered it in different ways: “grove” in the King James Version, “sacred pole” in many modern translations, reflecting the uncertainty about what exactly is meant. The ancient versions (Septuagint, Vulgate, Peshitta) also offer varying interpretations, generally leaning toward “sacred grove” or “wooded shrine,” further testifying to the difficulty of pinning down its precise meaning.

Saul M. Olyan, in his book Asherah and the cult of Yahweh in Israel, has argued that, despite this ambiguity, one feature is consistent: Biblical verbs used with asherah (“make,” “set up,” “cut down,” “burn”) suggest an Asherah wasn’t a living tree but rather a constructed cult symbol, likely wooden.

Hadley, however, cautions that not all biblical references can be reduced to a wooden Asherah pole or stylized tree.

In several cases, such as Asa’s removal of his mother Maacah for making a mipleset ‘for the asherah’ (1 Kings 15:13) or the mention of the ‘prophets of Asherah’ in Elijah’s contest on Mount Carmel (1 Kings 18:19), the term seems to point beyond an object to the memory of a divine being.

For Hadley, this reflects an important stage in the development of the term: in some contexts it denotes the goddess, in others the cult image, and eventually the distinction became blurred

Moreover, the Deuteronomistic historians (the authors and editors of Deuteronomy through Kings) regularly list the asherah in their catalogues of condemned practices, alongside Baal, the “host of heaven,” and child sacrifice.

That consistent pairing has led many scholars to conclude that the polemical rejection of Asherah wasn’t because she was foreign, but because she was intimately linked to Yahweh’s cult in ways that later reformers wished to suppress.

Furthermore, Hadley highlights that nearly all biblical mentions of Asherah occur in Deuteronomistic or post-Deuteronomistic texts. The striking silence of earlier prophetic writings such as Hosea and Amos (despite their zeal against Baal) suggests Asherah wasn’t initially considered illegitimate. Rather, her cult was systematically polemicized in later reform contexts, particularly under Josiah.

In Hadley’s view, the biblical evidence reflects a historical trajectory in the use of the term. Israel’s earlier traditions recalled an Asherah goddess, presenting her similarly to the Ugaritic texts.

Over time, her presence was increasingly mediated through a wooden cult symbol, poles or stylized trees erected beside altars. By the Deuteronomistic period, the polemical writers often referred only to the symbol itself, stripping it of divine identity.

The process left the biblical record in tension: at moments the goddess still flickers through, at others only the cult object remains.

Was Asherah Yahweh’s Wife?

Did anyone ever tell you that the Jewish God, the very one worshiped by Christians as well, and revered today by billions as the sole deity of the universe, might once have been married?

As strange as that may sound, this is precisely the conundrum that has animated scholarly debates for decades. Specialists in the history of Israelite religion have wrestled with a provocative question: was Yahweh, the God of Israel, once understood to have a divine consort named Asherah?

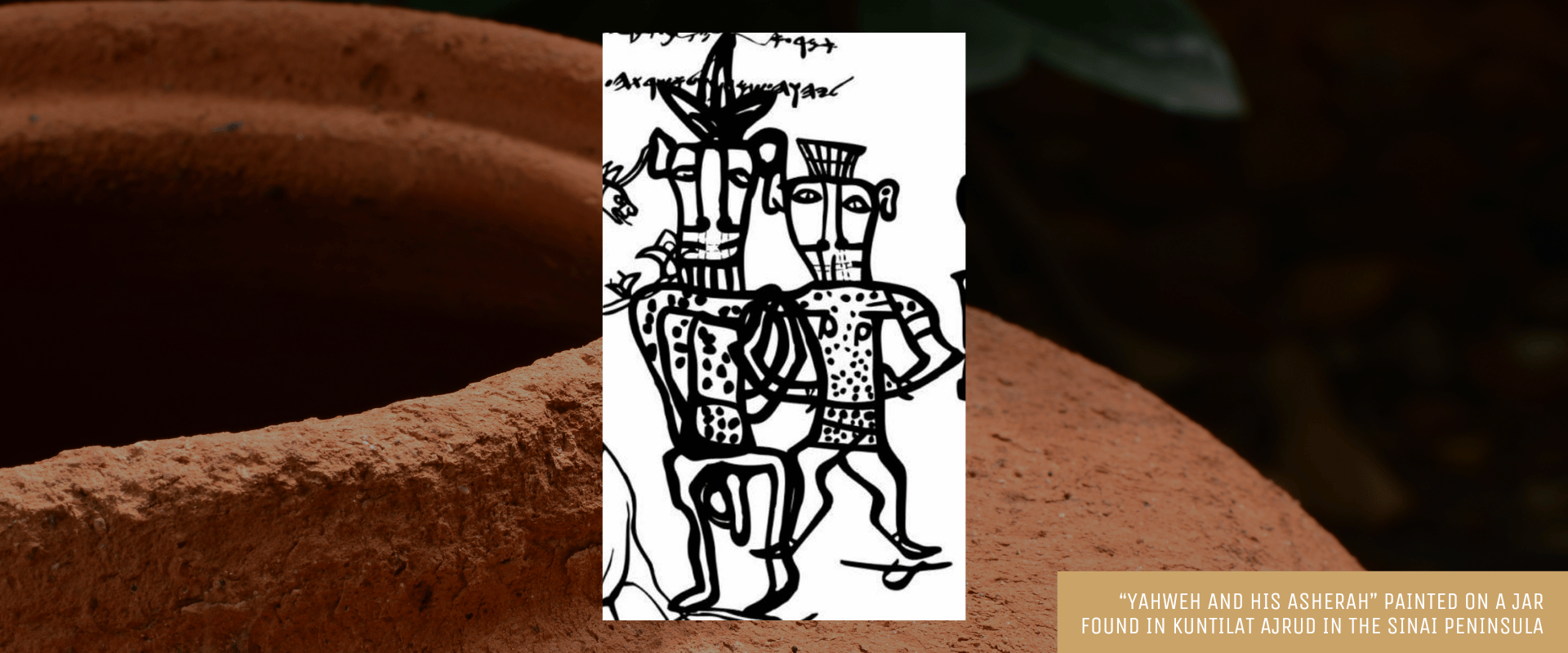

The controversy owes much of its spark to archaeological discoveries from the late 20th century. In the 1960s and 1970s, excavations at sites such as Kuntillet ʿAjrud in the Sinai desert and Khirbet el-Qôm in Judah revealed inscriptions dating from the 8th century B.C.E.

Several of them contain blessing formulas that pair Yahweh’s name with something or someone else. One text from Kuntillet ʿAjrud, painted on a large storage jar, reads: “I bless you by Yahweh of Samaria and by his Asherah.”

Another, from Khirbet el-Qôm, similarly invokes Yahweh and ʾšrth. Alongside the texts were drawings (most famously, a seated female figure on a lion throne) that fueled speculation. Did these inscriptions mean that Yahweh had a partner? Was Asherah his wife?

Here the scholarly consensus fractures. Virtually all agree that the inscriptions are authentic and significant but fiercely contest their interpretation.

For some scholars, the inscriptions provide direct evidence that Israelites in certain circles saw Asherah as Yahweh’s consort. For others, the key word ʾšrth refers not to a goddess at all, but to something quite different, perhaps a cultic object or even simply “his sanctuary.” Let us look at both sides of the debate.

William G. Dever, in his book Did God Have a Wife?, argues that the archaeological evidence clearly points to Asherah being venerated as Yahweh’s consort in popular religion.

He highlights the Kuntillet ʿAjrud inscriptions that explicitly read “Yahweh and his Asherah,” noting that in the surrounding iconography, the seated female figure on a lion throne can only be understood as a goddess.

In Near Eastern iconography, lion thrones were never used by ordinary mortals, only by kings and deities. For Dever, the clinching point is that Asherah was already known as the consort of El, the chief god of the Canaanite pantheon, and this tradition was carried into Israelite practice.

To interpret “his Asherah” as anything but a divine lady is, in his view, a retreat born out of modern discomfort. Dever concludes that the most straightforward reading is that many Israelites in the monarchic period did indeed believe Yahweh had a wife.

Others disagree. Émile Puech has revisited the Khirbet el-Qôm inscription and the parallel formulas at Kuntillet ʿAjrud, and he reaches a very different conclusion. For Puech, the grammar of the inscriptions points not to a second subject of blessing, but to a location.

He notes the consistently singular verb forms in the blessing formulas In other words, Yahweh alone blesses.

Moreover, comparative Semitic evidence shows that the root ʾšrh/ʾšrth can mean “sanctuary” or “holy place” in Phoenician and Aramaic.Puech argues that the same meaning applies here. Thus, the formula “Yahweh and his ʾšrth” should be translated as “Yahweh and his sanctuary.”

As Puech writes in his conclusion:

In the end, not only do these epigraphic testimonies reveal no cult of a divine couple – certainly not of the goddess Asherah as Yahweh’s wife or associate – but they converge in giving the term ʾšrth the sense of ‘his sanctuary.’ A translation such as ‘by his Asherah/idol/pole’ cannot be accepted, for an asherah does not bless or save. Consequently, these testimonies attest the sense of ‘sanctuary’ in Hebrew, just as in Phoenician and Aramaic. (my translation)

Where does this leave us? Both Dever and Puech marshal serious arguments, each grounded in archaeology, linguistics, and comparative religion.

For some, the image of Asherah as Yahweh’s Lady illuminates the lived religion of ordinary Israelites. For others, the grammar and comparative Semitic usage leave no room for such a pairing.

Since I am not an expert on the archaeology of ancient Israelite religion or the goddess Asherah, I’ll withhold judgment on whether she was truly understood as Yahweh’s wife. For readers who want to go further, Dan McClellan’s lecture “The Lost Goddess of Israel: Rediscovering Asherah” explores the evidence in far greater depth and offers his own conclusions.

Whatever the final word, the debate itself underscores how complex Israel’s religious history truly was. But before we draw our conclusions about Asherah’s role, we must turn to another key issue: How and why Asherah was eventually removed from Israel’s scriptures and its official religious memory.

Why Was Asherah Removed from the Bible?

The canonization of both Judaism and Christianity wasn’t a single moment in time but the result of long, complex processes involving diverse social, religious, and cultural forces. Ideas about which texts were authoritative, which traditions were to be preserved, and which practices were to be condemned developed gradually, often in response to internal struggles and external pressures.

The Israelite religion reflected in the Hebrew Bible didn’t spring forth as fully formed monotheism. Far from it!

It took shape over centuries, evolving in dialogue with surrounding cultures and in the crucible of reform movements that sought to establish sharper boundaries between acceptable and unacceptable expressions of faith.

In that light, it would be misleading to say that Asherah was simply “removed” from the Bible. After all, she wasn’t erased from the textual tradition altogether. Her name, as we mentioned, appears around 40 times. What did happen, however, was a deliberate campaign of polemical marginalization.

The Deuteronomistic authors and editors, writing and compiling their history in the late 7th and 6th centuries B.C.E., consistently grouped Asherah with practices they considered illegitimate: High places, sacred poles, standing stones, worship of the “host of heaven,” child sacrifice, and Baal.

In their narrative, Asherah becomes a byword for apostasy, her cult objects set up by unfaithful kings and torn down by the righteous reformers. The classic example is King Josiah’s purge (2 Kings 23), in which the asherah is removed from the Jerusalem temple and burned, its ashes scattered in the Kidron Valley.

Mordechai Cogan, in his Commentary, explains:

This Asherah image [explicitly mentioned in 2 Kings 23:6] had been installed by Manasseh (cf. 21:7 and see the note there). The repeated acts of destruction carried out against it – burning, grinding, scattering the dust – recall the description of the extirpation of the golden calf. In both Exod 32:20 and Deut 9:21, Moses is said to have burnt, ground to fine dust and scattered its remains ‘in the wadi that comes down the mountain.’’ In similar fashion, the writer relates that Josiah rid himself of the odious idol of Asherah.

How effective this polemic was is difficult to measure. Our written sources preserve the voices of those who won but not those of the ordinary men and women who may have continued venerating Asherah in homes and local shrines.

Still, the later biblical record is telling. Beyond the Deuteronomistic history and a handful of prophetic passages that reflect its influence, explicit polemic against Asherah virtually disappears.

Hosea and Amos, earlier prophets who inveigh against Baal and other foreign gods, do not even mention her. This silence may suggest that by the post-exilic period the campaign had succeeded.

Conclusion

The story of Asherah in the Bible illustrates how fluid and contested ancient Israelite religion really was. Archaeological discoveries, inscriptions, and the biblical texts themselves show that Israelite worship wasn’t monolithic but developed in a complex environment of negotiation between tradition and reform, popular practice and priestly ideology.

Whether Asherah was once understood as a goddess, a cultic emblem, or both, her presence and subsequent marginalization reveal the gradual process by which Israelite religion moved toward a more exclusive devotion to Yahweh.

Scholars remain divided (again: check out Dan’s excellent course!) over the inscriptions from Kuntillet ʿAjrud and Khirbet el-Qôm, some seeing evidence that Asherah functioned as Yahweh’s consort, others insisting that the term refers instead to a sanctuary or cult object.

What cannot be denied, however, is the important role that debates over Asherah play in uncovering Israel’s complex religious past!

join bart ehrman's new conference!

New Insights into the Hebrew Bible

March 20-22 | 13 Bible Scholars | Early-Bird Pricing

Inaugural conference will focus on the book of Genesis