Codex Sinaiticus: Our Earliest Christian Bible Manuscript

Written by Joshua Schachterle, Ph.D

Author | Professor | Scholar

Author | Professor | BE Contributor

Verified! See our editorial guidelines

Verified! See our guidelines

Date written: March 21st, 2024

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily match my own. - Dr. Bart D. Ehrman

Codex Sinaiticus is one of the oldest Bible manuscripts in existence. It is a fascinating text, and explains a lot about the formation of the biblical canon, ancient book production, and scribal culture. In this article, I’ll describe what the Codex Sinaiticus is (also known as the Sinai Bible), talk about its history, and discuss what it can teach us about the history of Christianity.

What Exactly is Codex Sinaiticus?

Codex Sinaiticus might be our earliest Christian Bible manuscript (the other candidate is the Codex Vaticanus). It was made in the 4th century CE and definitely contains our oldest complete New Testament manuscript (although it adds a couple of books. More on that later).

But what is a codex? A codex is an early form of the modern book. When Christianity was emerging, most important writings were preserved on scrolls. The codex (plural: “codices”) ultimately proved superior to the scroll, though, for several reasons.

First, you could open a codex to any page and more easily find a specific passage. It was much more difficult to do this with a scroll, which had to be unrolled sequentially until the desired passage was found. In addition, within a codex, you could write on both sides of the page. In a time when writing materials were prohibitively expensive, being able to optimize page space was a big advantage. Finally, codices were far sturdier and easier to transport than scrolls.

Codex Sinaiticus was written on vellum parchment, which was made of either calfskin or sheepskin. The codex is made up of quires – folded sheets of parchment – of eight pages each. These were then sewn together to bind the entire book.

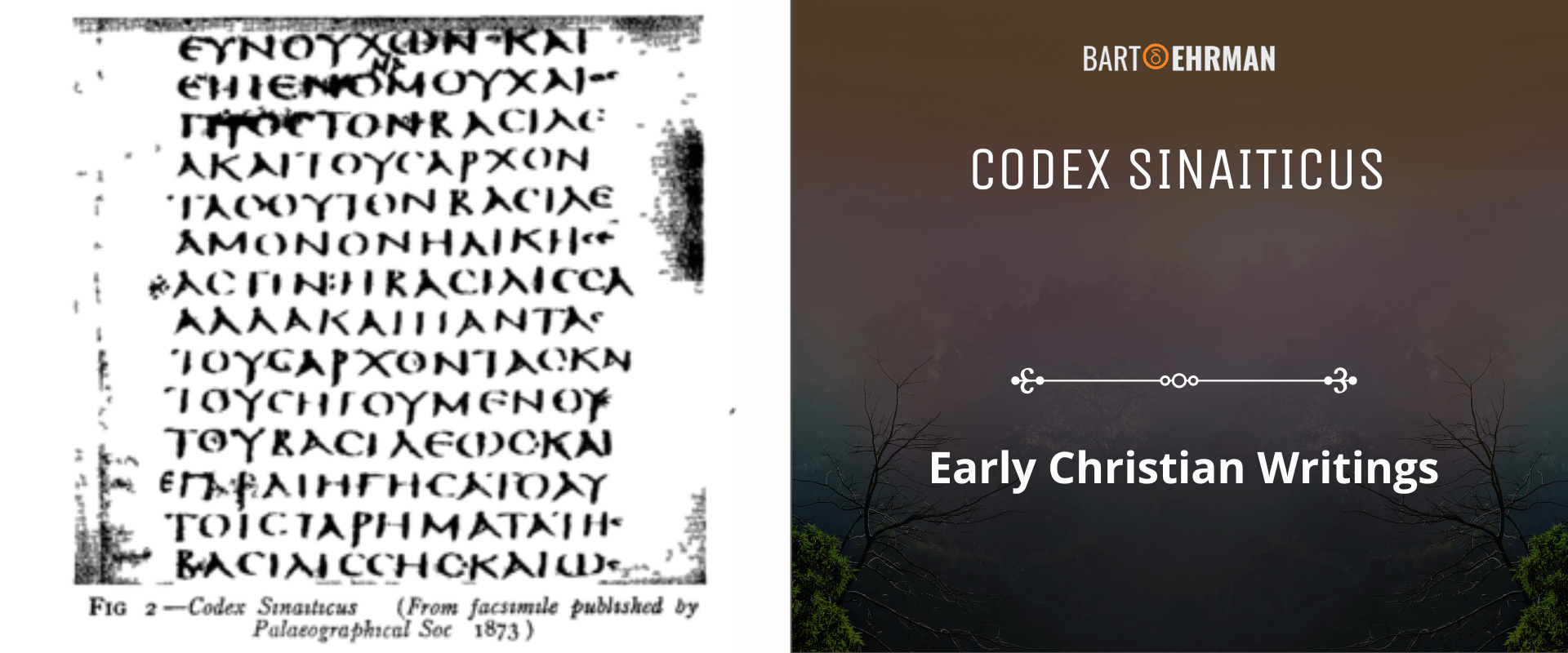

It was written entirely in Greek, with each page written in four columns. This means that it also includes a form of the Septuagint, the Greek form of the Old Testament. The Septuagint was the form of the Old Testament read and used as a source by Paul and other Greek-speaking New Testament writers.

Did You Know?

Most ancient Greek and Latin writings, including versions of the Bible, were written using scriptio continua (Latin for “continuous script”). This was a style of writing with no spaces between words and no punctuation. In addition, most of these ancient texts used majuscule script, meaning all the letters were capitalized.

The purpose of leaving no spaces between words in ancient manuscripts was to save space on the page. Writing materials, especially forms of papyrus and parchment were extremely expensive in the ancient world. However, this can cause problems for translators.

Consider this phrase, written in capital letters and scriptio continua:

GODISNOWHERE

Does it say “God is now here” or “God is nowhere”? Context clues obviously help translators to make the right decision, but it can be a difficult problem.

Where Did Codex Sinaiticus Come From?

The codex has an interesting history. While we can’t know for certain, some scholars believe it was originally written in Rome. It may even have been one of the 50 Bibles commissioned by the emperor Constantine, according to his biographer Eusebius of Caesarea.

It was discovered in 1844 by Constantin von Tischendorf, a German biblical scholar intent on finding the original form of the New Testament. On a visit to the library of St. Catherine’s Monastery in Egypt, he found 43 pages of a Greek Old Testament. On return trips to the monastery, he found sheets of the same manuscript comprising the New Testament.

The reason it’s called Codex Sinaiticus, or “Sinai Book”, incidentally, is because the monastery where it was found is at the foot of what was traditionally said to be the famous Mount Sinai where Moses talked with God and received the Torah.

Tischendorf took all these pages back to his university in Leipzig, Germany, where he eventually published a four-volume edition of it in 1862. While Tischendorf wrote that the monks gave the manuscripts to him, the monks at St. Catherine’s still say that he stole them, according to Bart Ehrman. See also this article about Tischendorf.

These days, the pages of Codex Sinaiticus are divided into four parts and held, conserved, and digitized by four institutions: The British Library, Leipzig University Library, St. Catherine’s Monastery, and the National Library of Russia. You can actually see the manuscript in digital photos on the Codex’s very own website codexsinaiticus.org. For Bible nerds like me, it’s pretty cool!

Why Is Codex Sinaiticus So Important? What Can It Tell Us?

Let’s start with the contents of the codex. Large sections of the Old Testament portion are missing but scholars believe the codex originally contained all of both the Old and New Testaments.

The Old Testament section is missing Exodus, Ruth, and several other books entirely. Many of the books included only contain fragments. This is the case, for example, with the entire Pentateuch, Joshua, Judges, 1 Chronicles, and Ezra-Nehemiah.

It also contains several Old Testament books considered apocryphal by Jews and most Protestants (although other Christians consider them as Scripture). These include Tobit, 1 and 4 Maccabees, the Wisdom of Solomon, and the Wisdom of Sirach. This is evidence that for at least some 4th-century Greek-speaking Christians, these books were considered scriptural.

On the other hand, the entire New Testament as we know it is included in the codex, as well as two extra books, the Shepherd of Hermas, and the Epistle of Barnabas. This demonstrates that in the mid-4th century when the codex was produced, those two books were considered Scripture, at least by some Christians. While the Christian canon was beginning to solidify, there were still clearly differences of opinion on what was Scripture and what wasn’t.

Although it contains all of our current New Testament books, Codex Sinaiticus also has a slightly different order from modern Bibles. The book of Acts, for example, which normally comes right after the Gospels, is moved between Philemon and James, while Hebrews is placed between 2 Thessalonians and 1 Timothy. This indicates that the proper order of books was still in flux as well.

Sinaiticus is also important for historians as an early example of ancient book production. While the codex was rebound at least once in its history, scholars can see how it was originally bound. In addition, Christian Scriptures were some of the earliest writings widely circulated in book rather than scroll form.

Omissions in Codex Sinaiticus

Several famous lines and/or passages are left out of Codex Sinaiticus compared with the King James Version which many English-speaking Christians still use. For example, the story of the woman taken in adultery from John 8 is not included in the codex. This isn’t a huge surprise, however, since all our oldest manuscripts of John are missing that story. The story was likely added to John much later by scribes.

The longer ending of the Gospel of Mark isn’t contained in the codex either. Instead, the codex’s version of Mark ends with verse 16:8 in which the women, after hearing the young man in white clothing speak of Jesus’ resurrection in the otherwise empty tomb, run away and tell no one. Another comparably ancient manuscript of Mark in the Codex Vaticanus, ends this way as well. For this reason, most scholars like Dale Allison assume this was the original ending of Mark.

Speaking of Mark, while the first verse of the King James Version of this Gospel begins with a reference to “Jesus Christ, the Son of God,” Mark 1:1 in Codex Sinaiticus omits “Son of God.” This would obviously have major theological implications were it not for the fact that just a few verses later, during Jesus’ baptism, God’s voice says that Jesus is his Son in Codex Sinaiticus.

In Luke 24:51, the King James Version says that Jesus was “parted from them, and carried up into heaven.” In the codex, however, the verse merely says that Jesus was “separated from them”. Since this is one of the oldest manuscripts we have of Luke, this may be the original form of the verse. Does it mean that Jesus merely walked away from the disciples rather than ascending to heaven? It’s unclear.

Finally, the Lord’s Prayer (or Our Father) in Matthew includes a last line of the prayer in the King James Version: “For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory forever.” This line is absent in this verse in the codex. I suppose this could have theological implications (maybe not affirming God’s power?). On the other hand, the manuscripts upon which the King James is based may simply have a scribal addition.

Scribal Corrections in Codex Sinaiticus

Another unique element is noted by the Codex Sinaiticus website: this Bible manuscript has been corrected by subsequent scribes more than any other Bible manuscript. In fact, D.C. Parker writes that there are over 27,000 such corrections! They are found most frequently in the Old Testament portion. According to the website, they range from the 4th century, near to the time the codex was first produced, all the way up to the 12th century. Some scribes merely changed a single letter while others inserted whole sentences.

As with most of these kinds of scribal changes, the majority don’t change the text’s meaning drastically, as Bart Ehrman says in Misquoting Jesus. However, there are examples where some of these corrections may be theologically motivated.

For example, in Matthew 24:36 where Jesus talks about the coming Kingdom of God, most translations read something like this: “But about that day and hour no one knows, neither the angels of heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father.” However, a second scribe marked the phrase “nor the Son” as doubtful, no doubt thinking that if the Son and the Father were equal, then the Son would know when the end was coming. A third scribe put the original phrase back in.

In some cases, scribes inserted phrases. Matthew 27:49, speaking about bystanders watching Jesus’ crucifixion, reads like this in most translations: “But the others said, ‘Wait, let us see whether Elijah will come to save him.’” However, a scribe added this line: “And another took a spear and pierced his side, and out came water and blood.”

This is a line directly taken from John 19:34, and doesn’t make much sense in Matthew. Unlike the crucifixion scene in John, the speakers in Matthew aren’t soldiers.

However, some, like the 3rd century theologian Origen of Alexandria, have interpreted the blood and water scene as significant evidence of a miracle, since blood in a dead body should have congealed rather than flowed. From that perspective, this addition could very well have been theologically motivated and seen as essential.

Corrections like these tell us something significant: scribes knew they didn’t have any original copies of biblical manuscripts and were thus still trying to decide what the originals said (or should say). They decided this based on the frequency of certain phrases in other manuscripts, but also in terms of theology. If a phrase didn’t fit with their own theology or that of their community, it might be omitted. Likewise, another phrase originally omitted might be added.

Conclusion

Codex Sinaiticus is an incredibly important early Christian artifact. From its pages we can learn a great deal about Christianity in the pivotal 4th century, a time that included the reign of the first Christian emperor, the Council of Nicaea, and myriad debates over which books were worthy of being called Scripture.

Codex Sinaiticus was discovered in St. Catherine’s Monastery in Egypt in 1844 by a biblical scholar named Constantin von Tischendorf. He wasn’t a disinterested observer, however. He was on a desperate quest to find the original text of the New Testament. Tischendorf may have simply stolen the pages from the Codex, but we can’t know for sure.

The codex was handwritten in Greek on parchment made from animal skins. It contains much of the Old Testament, as well as some apocryphal books, and all of our current New Testament with two additional books, all of which were apparently considered Scripture at the time.

Of all the early Bible manuscripts, Codex Sinaiticus has the most scribal corrections. These include removing lines that are found in most other manuscripts and adding lines from other Gospels or manuscripts. What this all goes to show is that even though the Christian canon was beginning to solidify in the 4th century, there was still a certain fluidity within the text, and certainly no universal agreement about it.