Seleucid Empire: Timeline, Rulers, and Historical Significance

Written by Joshua Schachterle, Ph.D

Author | Professor | Scholar

Author | Professor | BE Contributor

Verified! See our editorial guidelines

Verified! See our guidelines

Date written: January 4th, 2026

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily match my own. - Dr. Bart D. Ehrman

Stretching from the shores of the Mediterranean to the borders of India, the Seleucid Empire was one of the largest and most complex states of the ancient world. Born out of the disarray following the death of Alexander the Great, it was ruled by a dynasty that sought to preserve Greek culture while governing an extraordinarily diverse population across Asia and the Near East.

In this article I’ll explore the origins, rulers, and major turning points of the Seleucid Empire, tracing how it rose to power, struggled to maintain unity, and ultimately fell under the pressure of internal conflict and powerful rivals. By understanding this history, we can better comprehend the Seleucids’ lasting political, cultural, and economic impact on the ancient Mediterranean and beyond.

Background of the Seleucid Empire

As with much of ancient Mediterranean history, the story of the Seleucid (pronounced sell-OO-sid) Empire begins with Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE). As the King of Macedonia, Alexander spent 13 years conquering many lands. First, he defeated the vast Persian Empire, then went on to take control of most of Asia Minor, Egypt, the Levant, Babylonia, and Northern India. Along the way, he and his invading armies spread Greek language and culture, which would have a long-lasting effect on the Mediterranean world.

However, in 323, Alexander died in Babylonia of a mysterious illness. The empire he had built now had no dominant leader. Into this power vacuum stepped several of Alexander’s generals, sparking what would become known as the wars of the Diadochi (dee-ah-DOH-key), the Greek word for “successors.” Eventually, Alexander’s empire would be carved up, principally between three factions.

The land of Egypt would be taken over by the Ptolemies, ruled by general Ptolemy I Soter. Mainland Greece, Macedonia, and the surrounding Islands, meanwhile, would be controlled by the Antigonids, ruled by general Antigonus I Monophthalmus. Finally, Syria and other Near Eastern territories would be controlled by the Seleucids, ruled initially by Seleucus I Nicator. As you can see, the name of each ruling dynasty came from their founders and first rulers. Thus the Seleucid Empire was named for Seleucus I Nicator.

The Seleucid Empire as a relatively stable state was initially established in 311 BCE (although the faction of the Seleucids under Seleucus I began in 305 BCE) and would last some 250 years. In their book From Samarkhand to Sardis: A New Approach to the Seleucid Empire, scholars Susan Sherwin-White and Amélie Kuhrt note that ancient sources described the territory conquered by the Seleucids sometimes as an empire (Greek: archḗ) and others as a kingdom (Greek: basileía). Either way, to understand this empire/kingdom, we need to start with a brief biography of its founder, Seleucus I Nicator.

(Affiliate Disclaimer: We may earn commissions on products you purchase through this page at no additional cost to you. Thank you for supporting our site!)

Seleucus I Nicator: Founder of an Empire

While Seleucus (sometimes spelled Seleukus) was the general’s first name, “Nicator” was a title meant “victorious.” Seleucus was born in northern Macedonia to a noble family in 358 BCE. As an adolescent, he became the page of King Philip II, Alexander the Great’s father.

In his Roman History, ancient Greek historian Appian of Alexandria (95 CE-165 CE) includes a number of stories showing Seleucus’ strength. For example, when Alexander was about to sacrifice a bull, the bull broke away. Seleucus apparently recaptured the bull with his bare hands by grabbing its horns. While we can’t necessarily trust the historicity of such stories, it shows the image that Seleucus and his successors created and attempted to maintain for themselves.

In his early 20s, Seleucus joined Alexander’s military campaign as it entered Asia. By the time Alexander arrived in India, Seleucus had become one of Alexander’s most trusted generals, commanding an entire infantry core. However, after Alexander’s death, there were four overlapping wars of the Diadochi, as I mentioned above, between 322 and 301 BCE, after which the general territorial boundaries for each of the three principal successors – Ptolemies, Antigonids, and Seleucids – were established. Their borders would remain flexible, however, as each dynasty would conquer and lose territory throughout their histories.

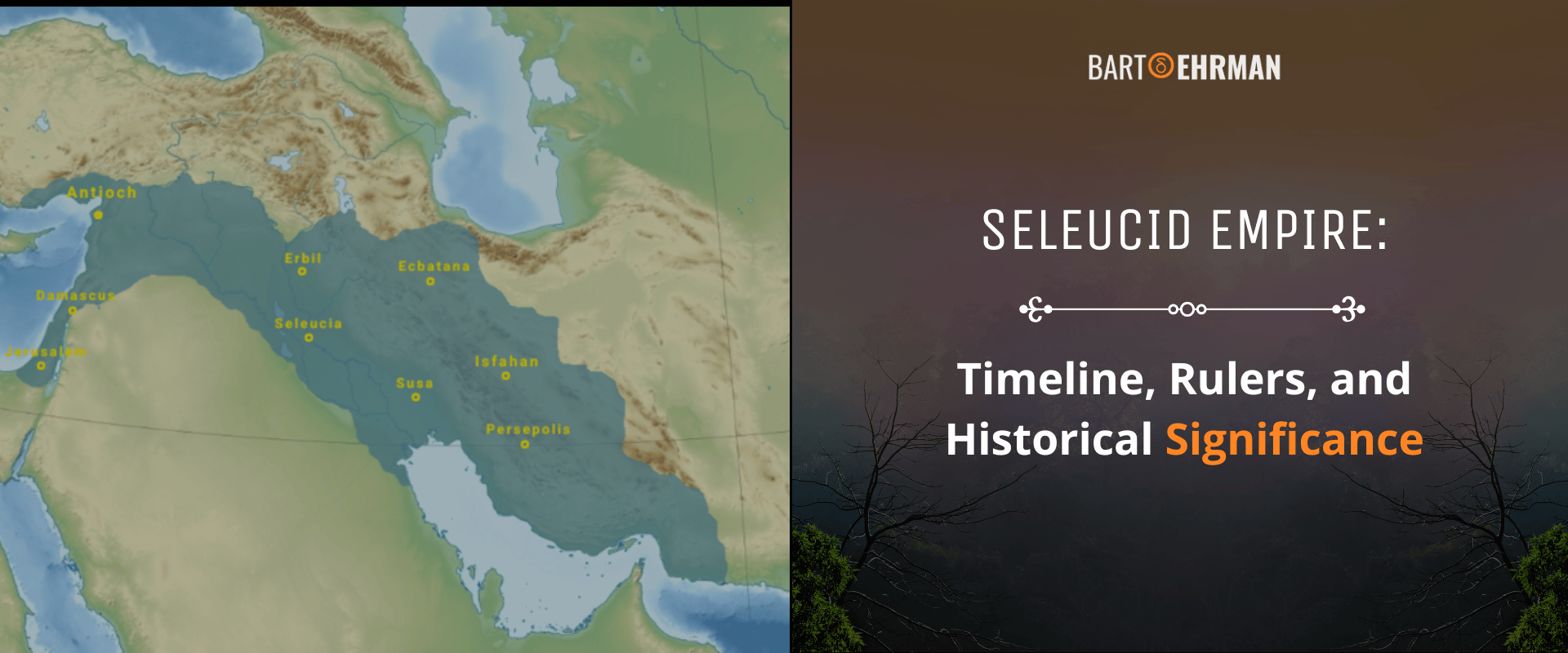

We can look at a Seleucid Empire map to see how much territory the empire covered. At its greatest extent, the Seleucid territories included Thrace (modern Bulgaria, Greece, and European Turkey) to the Indus River valley (modern Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan), Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), Syria, Iran, and Afghanistan, plus parts of Lebanon, Central Asia (modern Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan). The Seleucids’ major capitals were Antioch, Syria and Seleucia on the Tigris river in Iraq, both of which were built by Seleucus I. Writing long after the death of Seleucus, famed Greek geographer Strabo (63 BCE-24 CE) wrote that Antioch remained the capital city of the empire:

Antioch is the metropolis of Syria, and the king’s residence (basileion) was founded here for the rulers of the land, and in power and size it is not far short of Seleukeia-on-Tigris and Alexandria-by-Egypt.

At its peak, the Seleucid Empire was the largest of the three successors’ empires. Beyond simply founding this dynasty, Seleucus I would also rule it longer than any other Seleucid ruler – about 30 years – and conquer more territory than any other Seleucid king as well.

Seleucus I Nicator was assassinated by a member of the Ptolemaic dynasty in 281 BCE.

Seleucid Empire Rulers and History

I’ll now explain some of the most important Seleucid rulers. Below is a chart listing the Seleucid kings in chronological order:

Ruler | Years of Reign |

|---|---|

Seleucus I Nicator | 305-281 BCE |

Antiochus I Soter | 281-261 BCE |

Antiochus II Theos | 261-246 BCE |

Seleucus II Callinicus | 246-225 BCE |

Seleucus III Ceraunus | 225-223 BCE |

Antiochus III the Great | 223-187 BCE |

Seleucus IV Philopator | 187-175 BCE |

Antiochus IV Epiphanes | 175-164 BCE |

Antiochus V Eupator | 164-162 BCE |

Demetrius I Soter | 162-150 BCE |

Alexander I Balas | 150-145 BCE |

Demetrius II Nicator | 145-138 BCE |

Antiochus VII Sidetes | 138-129 BCE |

Demetrius II Nicator | 129-125 BCE |

Antiochus VIII Grypus | 125-96 BCE |

Antiochus IX Cyzicenus | 114-95 BCE |

Seleucus VI Epiphanes | 96-95 BCE |

Antiochus X Eusebes | 95-92 BCE |

Demetrius III Eucaerus | 95-87 BCE |

Antiochus XI Epiphanes | 94-92 BCE |

Philip I Philadelphus | 95-83 BCE |

Antiochus XII Dionysus | 87-84 BCE |

Tigranes II of Armenia (ruled Syria only) | 83-69 BCE |

Antiochus XIII Asiaticus | 69-64 BCE |

Philip II Philoromaeus | 65-63 BCE |

In a short article like this, it’s impossible to analyze the rule of each of these kings. However, we can certainly examine some of the more impactful events of the dynasty’s 250-year history.

Seleucus’ son, Antiochus I Soter, succeeded his father on the throne – although he had already been co-ruler with his father for almost a decade – but seems to have been less capable than his father at holding the empire together. Sherwin-White and Kuhrt note that after Seleucus’ death, people in several areas of the empire revolted, prompting Antiochus I to go around putting out metaphorical fires. Antiochus did manage to build new cities in Iran and Asia Minor, however.

At the death of Antiochus I in 261 BCE, his son Antiochus II Theos took over, spending much of his reign fighting against the Ptolemies, although like his father, he was faced with multiple regions attempting to claim independence from the larger Seleucid Empire.

In 246 BCE, Antiochus II died and his son Seleucus II Callinicus took the throne. Seleucus II was soon defeated by the Ptolemaic king Ptolemy III of Egypt. He then had to fight a civil war against his own brother Antiochus Hierax for the throne, a war Seleucus II won. However, all these battles distracted the king, which allowed more regions of the empire, especially in Asia Minor, to revolt.

Antiochus III the Great

Seleucus’ son Antiochus III the Great took over in 223 BCE and would prove to be the most successful Seleucid ruler after Seleucus I. He would spend the next ten years of his reign traveling over the eastern parts of the empire and restoring control to regions that had rebelled.

In 205 BCE, the Ptolemaic king Ptolemy IV died, prompting Antiochus III to consider expanding Seleucid territories westward. Antiochus and the Antigonid ruler Philip V of Macedon formed an agreement to divide the Ptolemaic lands that weren’t part of Egypt. Following that, the Seleucids expelled Ptolemy the IV’s successor, Ptolemy V, from a region called Coele-Syria (modern Lebanon and parts of Syria) after winning The Battle of Panium in 200 BCE. After several successive Seleucid rulers had lost a certain amount of control over their territories, To many, Antiochus seemed to have reestablished the Seleucid Empire’s power on par with Seleucus I.

Meanwhile, after Rome, the new rising power in the Mediterranean region, defeated Antiochus’ former supporter Philip V in 197 BCE, Antiochus made plans to take over Greece, a conquest which would have cemented the Seleucid Empire as the premier power of the Hellenic world inherited from Alexander. Unfortunately for him, Rome had other ideas. According to Graham Shipley in his book The Greek World After Alexander 323-30 BC,

The event for which Antiochos III is best remembered is his war against the Romans between 192 and 189, culminating in his defeat at Magnesia in western Asia Minor (early 189). By the peace of Apameia (188) he gave up most of Asia Minor, which was divided between Rhodes and Pergamon. Within a year he died. These are often seen as fatal blows for the Seleukid empire, the beginning of the end; it remained a large kingdom for another century, but had lost one of its most valuable possessions, Asia Minor.

Although he had clearly achieved during his reign, Antiochus III’s achievements were offset by his ultimate defeat and the loss of a massive amount of territory to the Romans. In addition, as part of the peace treaty with Rome (the Treaty of Apameia), the defeated Seleucids agreed to pay Rome a large indemnity – a punitive payment to cover Rome’s financial losses in the war.

Antiochus’ son and successor, Seleucus IV Philopator, would spend his entire reign trying to pay off this indemnity. When he was assassinated in 175 BCE, he was succeeded by his brother, the most famous – or perhaps infamous – Seleucid ruler of all: Antiochus IV Epiphanes.

Antiochus IV Epiphanes and the Maccabean Revolt

Antiochus IV began his reign by trying to reclaim the empire’s former glory. He initiated a war against the Ptolemies in Egypt in which he was able to take all of Egypt except the city of Alexandria. Nevertheless, according to 1st-century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, just before Antiochus was about to attack Alexandria, he was intercepted by an envoy from Rome named Popilius who showed him a senate decree:

The decree demanded that he should abort his attack on Alexandria and immediately stop waging the war on Ptolemy. When the king said that he would call his friends into council and consider what he ought to do, Popilius drew a circle in the sand around the king's feet with the stick he was carrying and said, "Before you step out of that circle give me a reply to lay before the senate." For a few moments he hesitated, astounded at such a peremptory order, and at last replied, "I will do what the senate thinks right." He then chose to withdraw rather than set the empire to war with Rome again.

During Antiochus’ journey back to the Seleucid capital of Antioch, Josephus, in his historical work The Jewish War, says Antiochus made a voyage to the Syrian territory of Judea, violently taking over Jerusalem, killing many inhabitants, suppressing traditional Jewish practices, and defiling the Jerusalem Temple. This would provoke the Maccabean Revolt, a successful Jewish rebellion against Antiochus. In the meantime, the rest of the empire was weakening as more and more territories rebelled. Antiochus IV Epiphanes would die during one of his attempts to retake a rebellious territory in 164 BCE. What followed was a series of short-lived rulers plagued by internecine fighting for the throne.

Antiochus VII Sidetes

In 138, Antiochus VII Sidetes took the throne after his brother, the ruler Demetrius II Nicator, had been captured in battle. He inherited an empire under many threats from the Maccabees and the Parthians, among others.

Antiochus first embarked on an effective military campaign in which he managed to reestablish control over several regions, including Mesopotamia, Babylonia, and Media. However, in 130 BCE, his troops were attacked by the Parthians and he was killed in battle in the city of Ecbatana in 129 BCE. Antiochus VII Sidetes would thereafter be called the last great Seleucid king. In the aftermath of his death, the Seleucid Empire fall began in earnest.

The Seleucid Empire Falls

From 100-63 BCE, the Seleucid Empire gradually broke apart as their territories were forcibly taken by the Parthians, and others. Civil wars and revolts continued to weaken the empire. Noting all this civil strife, King Tigranes II of Armenia, attacked and conquered Syria in 83 BCE, becoming its sole ruler.

In the meantime, the Romans, who had conquered most of the territories around Syria, got nervous about all the political volatility in Syria. The Seleucid Empire was finally put out of its misery by the Roman general Pompey in 63 BCE. Pompey saw the Seleucids as more trouble than they were worth. He deposed the remaining Seleucid ruler and abolished the monarchy, turning Syria into a Roman province.

Conclusion

The Seleucid Empire, short-lived as it may have been by historical standards, had a major impact on the history of the Mediterranean world. They spread Greek language and culture over vast territories. This is one reason Greek remained the dominant language of the eastern Mediterranean, contributing to the New Testament being written in Greek.

Additionally, as a military powerhouse, the Seleucids controlled key trade routes, managed rich agricultural lands that were exported to many regions, and issued Greek coinage. In other words, they had a major economic impact on the world.

Finally, they were a bridge to later civilizations. Not only did the empire's territories become vital for later empires like the Romans, but classical Greek learning, preserved by the Seleucids, was later translated into Arabic in Islamic academies, eventually even influencing the European Renaissance. While the empire was certainly messy – as all empires are – the Seleucids, perhaps unwittingly, provided the military, economic, and cultural foundations for much of future history.