What Was the Original Language of the Bible? (Old & New Testament Answers)

Written by Marko Marina, Ph.D.

Author | Historian

Author | Historian | BE Contributor

Verified! See our guidelines

Verified! See our editorial guidelines

Date written: November 10th, 2023

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily match my own. - Dr. Bart D. Ehrman

In a world where the Bible has been published in over 1200 languages, it's astounding to reflect on its ancient origins and development. In this article, we'll unveil the linguistic origins of both the Hebrew and the Christian Bible, exploring their unique features and significance.

Join us on a captivating voyage that traverses ancient languages, parchment scrolls, scribal intentional and unintentional mistakes, theological polemics, ancient translations, and amazing archeological discoveries.

Our journey begins with the fascinating question: What language the Bible was first written in? Let's embark on this historical expedition to uncover the foundations of a timeless and universally cherished text, from the original language of the Bible to the pivotal translation work of figures like Jerome and the emergence of the Latin Vulgate.

Defining Terms: What is the Bible?

Before we begin, it’s important to explain what the “Bible” is. The Christian Bible consists of the Old Testament (Hebrew Bible) and the New Testament. Together, the canon of the Christian Bible includes 66 (Protestant) or 73 (Catholic) books. The Hebrew Bible (with three sections known as Torah, Nevi’im, and Ketuvim), is the religious cornerstone of the Jewish people.

So, our exploration of the original language of the Bible will include both the Hebrew and the Christian Bible. We’ll uncover different developmental paths and historical circumstances that shaped both of these traditions in a particular way!

The Original Language of the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible, as shown in our earlier article, was composed over several centuries. It took even more time for the canonization of the Hebrew Bible - a process that probably began before Christianity even appeared.

Hebrew is the original language in which the majority of the Old Testament's books, including the Torah (the first five books), historical writings, prophetic texts, and poetic literature.

Hebrew is one of the oldest known languages, and its origins can be traced back to the second millennium BCE. It belongs to the Semitic language family, which includes other languages like Aramaic, Akkadian, and Arabic. Furthermore, Hebrew is written from right to left and uses a unique script known as the Hebrew alphabet, which consists of 22 letters.

However, it’s important to note that some parts of the Hebrew Bible (e.g. the Book of Daniel) were partially written in Aramaic - another Semitic language that later became the spoken language of the Palestinian Jews. Jesus of Nazareth, of course, preached in Aramaic.

In his Commentary on the Book of Daniel, John J. Collins observes that Daniel is bilingual, being partly in Hebrew and partly in Aramaic. This phenomenon, Collins notes, has given rise to numerous theories, which inevitably involve broader questions of the composition history of the book.

Consequently, one could argue that the language the Bible was first written in was Hebrew and then Aramaic. But Jews also recognized the practical advantages of subsequent translations of the Scripture.

Early Translations of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament)

In contrast to the Islamic position which demands that the only authentic version is the Arabic Quran, Jews and Christians accepted translations as the authentic words of God. In other words, both of these traditions canonized compositions and not the languages. They understood that moving from the original language of the Bible doesn’t necessarily contaminate God’s word.

In addition to Hebrew, the Bible language, Jews developed three ancient versions or translations.

These translations and revisions reveal a fascinating historical sequence. Notice that the Greek translation from the original Hebrew which began in the 3rd century B.C.E. reflects a period when Judaism was still an “equal player” among religious sects of the Roman Empire. It’s the same with the Aramaic translation completed in the 1st century C.E.

The second time translations happened was with Arabic and the arrival of a new religious movement or Islam which was based on the Arabic language. For the Jews living in the Near East area under the authority of Islamic invaders, the Arabic translation of the Bible was much needed.

So, these Jewish translations from the original language of the Bible can be seen as rhetorical strategies to preserve the stability and prosperity of their religious communities.

The Original Language of the Christian Bible (New Testament)

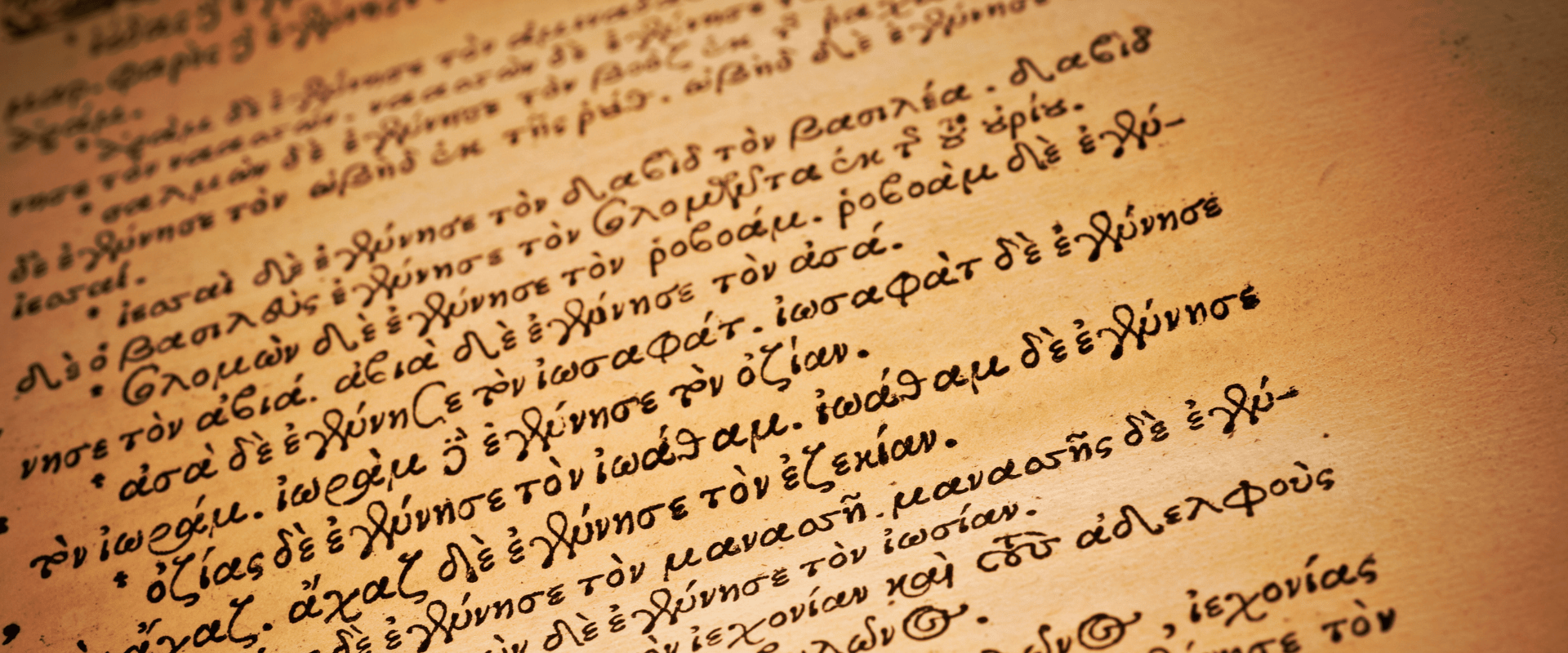

The original language of the Christian Bible (the New Testament) was Koine Greek. Koine Greek is a variant of the Greek language that emerged in the Hellenistic period, roughly from the 4th century BCE to the 4th century CE. It was a simplified and widely spoken form of Greek that developed as a lingua franca in the eastern Mediterranean and the Near East following the conquests of Alexander the Great (356.-323. B.C.E.).

The choice to use Koine Greek for the New Testament made the message of Christianity more accessible to a broader audience. In other words, it was a rhetorical strategy to reach a wider audience.

However, despite being written in Koine Greek, the New Testament documents contain elements of Semitism or the Aramaic language. This is especially vivid within the Synoptic Gospels.

For example, in Mark 5:41, when Jesus raises a young girl from the dead, he says, "Talitha koum," which is an Aramaic phrase that Mark transliterates into Greek. In other words, the author of the Gospel of Mark sometimes retains Aramaic phrases that were significant in the context of the narrative.

Furthermore, these Semitic traces, as Dr. Ehrman notes in his bestseller Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium provide another criterion for establishing the authentic parts that could be traced to the historical Jesus.

Early Translations of the Christian Bible: from Old Latin to Vulgate

The Latin version of the Christian Bible arose in the heart of the Roman Empire and eventually became the most important translation. It also reflects early Christian steps from the original language of the Bible.

To understand the development of this process we need to comprehend basic historical circumstances.

When Emperor Constantine (c. 280.-337. C.E.) shifted his capital to Constantinople, the Church in the east remained Greek-speaking. In other words, Christians there continued to read Septuagint and the New Testament in Greek - the original language of the (Christian) Bible.

Furthermore, eastern Christianity had a tremendous continuity of language and literature. Consequently, the Greek written and spoken in the 6th century, for instance, was the same Koine Greek in which the New Testament had been originally written.

The situation in the Western part of the Roman Empire, however, was different. In the absence of the emperor (since the middle of the 4th century), the bishop of Rome exercised supreme ecclesiastical and increasingly strong political authority.

Moreover, as the East remained exclusively Greek, the West became increasingly Latin. The adoption of Latin as the official language of the Bible represented an important aspect of the growing cultural distance between Eastern and Western Christianity. This distance eventually led to a schism in the middle of the 11th century.

The Earliest Latin Translations of the Bible

The beginning stages of the Latin Bible in the West are obscure. Latin is the ancestral (Indo-European type) language of Rome. Already during the Republic and before Christianity ever emerged, Romans had developed a great literature in Latin (e.g. Cicero’s Orations).

We can speculate that the earliest Latin translations of the Bible appeared in the 2nd century C.E. However, it’s not that clear where it happened. Most scholars believe that North Africa is the best hypothesis. It’s an educational guess based on several key observations:

The proliferation of many early Latin translations that scholars call “Old Latin” versions is remarkable. They show that the early Christians weren’t at all bound by the original language of the Bible.

As it turns out, such a proliferation caused the need for a standard Latin translation (Vulgate) done by Jerome. We’ll get back to him soon!

Did You Know?

Although he translated from the Hebrew original, Jerome was subtle in the manner in which he rendered key prophetic texts at certain points. For him, it was crucial to retain the validity of Jesus’ prophecy fulfillment. In Isaiah 7:14, for instance, Jerome’s Vulgate translates the Hebrew “almah” (young girl) as “virgo” (virgin). Thus, he pushed the Hebrew in the direction of Septuagint to preserve the Christian meaning of the text!

Additionally, many Christian authors of Late Antiquity recognized that these “Old Latin” versions suffer from poor quality. They were far from the language the Bible was first written in. An excellent example of this comes from the Old Latin manuscript known as Codex Veronensis.

Check out noticeable and important differences in the prologue of John (1:12-13) between the original Greek text and the Codex Veronensis.

My translation (based on the original Greek text) | My translation (based on the Latin text of Codex Veronensis |

|---|---|

But whosoever accepted him (ὅσοι δὲ ἔλαβον αὐτόν), he gave the power to become Children of God, to those who believe (τοῖς πιστεύουσιν) in his name who were begotten not of blood nor of the flesh nor of human will but out of God. | He gave them power (dedit eis potestatem) to become Children of God to those who accepted him, who was born (qui natus est), not of blood nor of the flesh nor of the will of man but out of God. |

Notice the singular (qui natus est) in the Old Latin version. It differs from the original language of the Bible which clearly identifies those (plural) who believe (τοῖς πιστεύουσιν) with those who were begotten. Why did this happen?

This shift to the masculine singular in the relative clause makes the antecedent of that clause “the word of God” and, therefore, makes the statement about “being born not of the blood…but of God” a statement about the virgin birth of Jesus.

This serves as a compelling example of how scribes, driven by theological motivations, purposefully altered the scriptural text to accentuate their religious doctrines.

If you want to know more about the world of early Christian scribes and the way they changed the text of the Bible, join Dr. Ehrman’s new course “The Scribal Corruption of Scripture”. As a renowned scholar of early Christianity, Bart provides captivating facts behind the story of who changed the Bible and why.

Vulgate: An Accomplishment of the Century

In response to the concerns about the variegated forms of Old Latin versions, Pope Damasus (c. 304.-384. C.E.) assigned his brilliant secretary Jerome the task of translating the Bible into a standard Latin version that became known as the Vulgate. Again, Christian religious authorities had no problem moving from the original language of the Bible as long as the translation had linguistic and theological merits.

Damasus could hardly pick a better person for this job. Jerome was a savant, an amazing scholar well-versed in Greek, Hebrew, and Latin. Furthermore, he was a prolific author who wrote numerous tractates, letters, and commentaries. In simple terms: Jerome was an intellectual superstar!

He began with a revision of the Gospels using the original language of the Christian Bible (Greek) in 382 C.E. After that, revisers who worked under Jerome’s supervision and guidance translated the rest of the New Testament.

Jerome then turned to the Old Testament. But he began translating it into Latin by using Septuagint - a Greek translation. He translated the Psalms in that way thus creating an edition known as Gallican Psalter.

However, Jerome soon became convinced that the original language of the Hebrew Bible was superior to the Septuagint. Consequently, he began a new, fresh translation of the Old Testament from the original language. This task occupied him for 15 years.

The earliest form of the complete Vulgate we have dates from the 6th century. It’s known as the Codex Amiantinus and it originally contained three copies of the Bible commissioned by the Abbot Ceolfrith in England.

Jerome’s version eventually became the standard Latin version and it lasted throughout the Middle Ages. It partially succeeded because of the ecclesiastical support. But the most important reason was the Vulgate’s intrinsic quality both in linguistic and theological dimensions. To put it more bluntly, Jerome was an amazingly skilled translator and theologian.

He had a deep insight into the meaning of Greek and Hebrew. Jerome even consulted with the Jewish rabbinic scholars on certain aspects of the Hebrew Bible. Moreover, his mastery of Latin enabled him to render Greek and Hebrew in a vigorous and idiomatic Latin that had genuine literary merit!

The best illustration of Jerome’s profound linguistic knowledge can be found in the introduction of Genesis: “In the beginning, God created heaven and earth”. Jerome recognized the deep meaning of these verses and translated them as: “in principio creavit Deus caelum et terram”.

By using the phrase “in principio”, Jerome brilliantly uncovered the meaning of the original Hebrew. It’s not simply at "the start of things" but also as "the basis of everything". God created everything because He is the basis of everything there is. And the phrase “in principio” encapsulates both of these meanings.

Have you ever wondered where the boundaries between history and myth lie in the Book of Genesis? Join Bart Ehrman's online course "In the Beginning: History, Legend, or Myth in Genesis?". You might be surprised by what you discover!

Jerome’s Vulgate became the source of liturgy for Christians during the Middle Ages. It was, the Bible of Western Europe from the 6th to the 16th century; from St. Benedict to Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation.

Summing up conclusion

The Bible, today translated into over 1200 languages, has a rich and intricate linguistic history. Our quest began with the intriguing question: "What language was the Bible first written in?" We've embarked on a journey that spans millennia, exploring the foundational languages of both the Hebrew and Christian Bibles, and the fascinating paths they took.

The Hebrew Bible, with its roots stretching back to the second millennium BCE, was primarily composed in the ancient Hebrew language. The original language of the (Christian) Bible was, on the other hand, Koine Greek - a lingua franca of the Roman Empire. Yet, Koine Greek doesn't stand alone; it carries hints of Semitism and Biblical Aramaic, notably within the Synoptic Gospels.

In conclusion, the original language of the Bible holds a profound significance in understanding the history and development of both the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures. While it may have started in ancient Hebrew and Koine Greek, the Bible's journey through translations and scribal influences left an indelible mark on the most popular and widely read book in history!